Bold new course model turns George Brown’s game design on its head

Class has just finished, but no one is packing up to leave. There’s bugs in the code, hit-detection is shoddy and the audio hasn’t even been added yet. There’s so little time and so much to do. But what do you expect when your task is to make a video game in a week?

It seems like an impossible challenge at first glance, but talk to anyone in video games and they’ll be familiar with the concept of a game jam. A timed challenge, a game jam tasks its participants with completing a fully-functioning game completely from scratch, in as little as 24 hours.

Game jams are both reviled and loved for their sadistic time constraints. It’s a model that emphasizes creative problem solving, and the cutting of every possible corner to deliver a finished game.

Toronto’s TOJam is one of the biggest jams in the world, but for students in George Brown College’s (GBC) game design program, that’s no big deal. After all, in their program, there isn’t just one game jam. Instead of typical coursework, the main assignments in this program are weekly game jams. That means making a new game, from concept to finished product, in seven days.

“I think it’s great. It’s very hands-on, and they don’t baby us or hold our hands whatsoever,” said Chris Blouin, one of the students in this year’s program. “They really throw you into the ocean and they don’t care if you swim or not. It’s very challenging, but it’s also very rewarding.”

Blouin added that even in the early stages of the program, he already feels as if he’s moving “closer to forming a career.”

Chris Blouin working on an animation loop for one of his games. Photo by Malcolm Derikx / The Dialog

The program’s current model is the brainchild of Jean-Paul Amore, GBC’s interactive digital design program co-ordinator. After assisting with the first TOJam in 2006, Amore has seen the event grow from a modest 20 participants to over 450 in its tenth iteration, which took place in May at GBC. Taking the concept of TOJam and retooling the game design program from a lecture-orientated program to a game jam model, the decision was simple for Amore.

“You’re a post-grad student, you’re here to work,” Amore said. “The value for the students, whether they realize it now or not, will become apparent next August. Ultimately they’re going to have games they can sell.”

Amore isn’t exaggerating. Last year’s weekly jams created roughly 70 games over the course of the program, and this year is on track to equal if not surpass that number. It’s a crash course in game creation not often seen in the academic world, but the practicality of it can’t be denied.

“The way to get better at making games is by making games,” said Adam Clare, a professor in the game design program, bluntly. Clare is one of the founders of the Toronto Board Game Jam, and the producer of Wero Creative’s Rock Mars. Clare specializes in the examination of video games; how we interact with them, design and play them.

“What I’m looking for from them is questions like, is this game interesting for the game industry at large to look at? Does it propel something forward, does it start a new conversation? Is it a reflection on something happening in the industry? Or does it help bring attention to the designers themselves?”

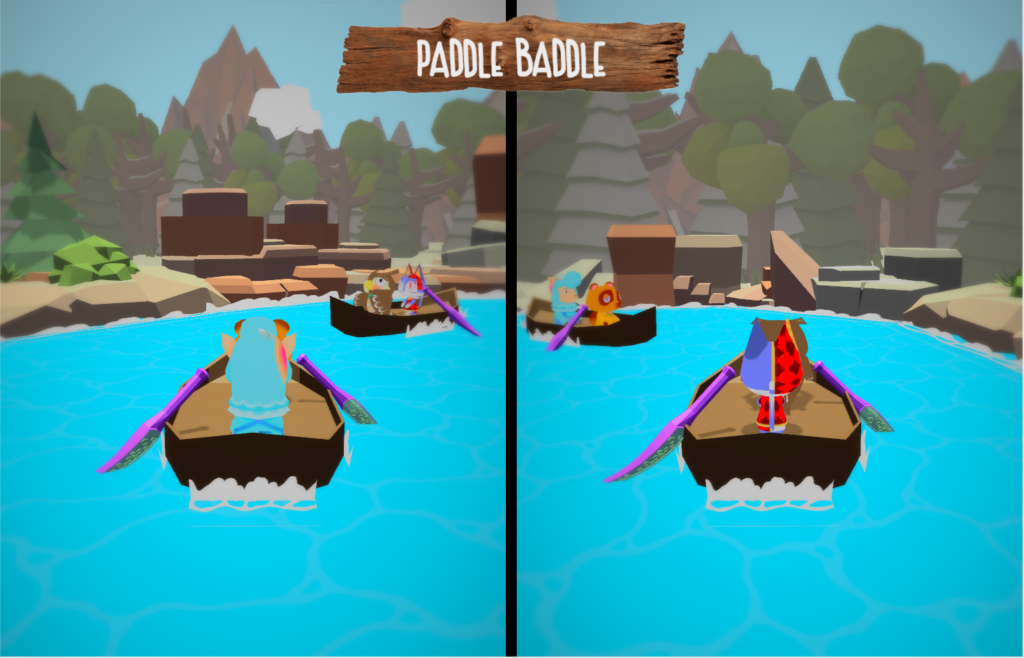

Every Thursday, Amore and Clare visit the students to see their completed projects. Walking the room with Clare, we tested several games. After losing terribly to him in Paddle Baddle, a four-player paddle-boat battle game, Clare let me know that Amore had approved the game for what’s called production in the George Brown jams, meaning the game would be reworked over the course of the year into a more refined product.

Rebbecca Mitchell, one of the creators of Paddle Baddle, was one of the few students aware that the game design program would involve game jams. In fact, it was part of the reason she applied.

Mitchell said when she was in game programming at the college, she was recruited as an intern to work with a previous year’s game design studio, 13AM Games. Seeing the development of their games sparked her own interest in the program, and led to her enrolment. Students in the game design program must recruit students in other George Brown programs, such as game programming and game development, to help them refine the games put into production.

The “Paddle Baddle” game was developed by GBC game design students in a recent Game Jam where they build a video game from scratch every week.

The formula is meant to simulate an actual studio environment as closely as possible, giving the students a chance to familiarize themselves with the jobs and responsibilities they’ll encounter in the field. The students are encouraged to run the class like a studio, even picking a company name.

It’s a method that has already developed winners- 13AM Games, the creators of Runbow and Pirate Pop Plus, is made up of George Brown graduates from the program. Taking part in the 2014 Global Game Jam, the group created the initial concept of Runbow, a platform-racing game with a focus on colour. Two years later, the game has been released on Wii U, and there was an announcement trailer at E3 2016 for Runbow Pocket, a New Nintendo 3DS port.

“I chose George Brown because I looked at the other colleges offering similar programs, and it just wasn’t impressive,” said Ian Norton, a game design student who specializes in sculpting and 3D modelling. “I know people who’ve gone here for game development and have worked with the game design people. People come out of here and they get jobs.”

Canada boasts one of the largest video game industries in the world, with over 470 active studios according to a 2015 survey by the Entertainment Software Association of Canada (ESAC). Of these companies, 23 per cent were located in Ontario, with over $265 million dollars in expenditures, and 2,500 full-time employees. This was a 26 per cent increase in employees since 2013. And with over 70 per cent of these new hires coming from the local scene, plus no signs of the industry boom slowing down, it’s a good time to be involved in games in Toronto.

Although still early in the semester, camaraderie is already forming among this year’s students. “We all come from a variety of disciplines, and they all have their own different perspectives,” said David Tamayo. “Seeing how others start their game process, or creative process, is really eye-opening.”

Tamayo’s project, Lyra, is one of the games slated for production this year. “It takes place in a world where all the music and all the audio of the world has been taken away. As the main character, Lyra, you have to venture around the world and investigate what happened to the music, where it’s gone,” Tamayo explains. “Because it’s a game jam model there’s little expectation regarding polish – the main point is to convey the mechanic to see if it’s fun.”

“When we outline each game jam, there are certain requirements such as software skills,” explains Clare. “The requirements come from professors in the program, and then some from what we’ve noticed they’re lacking in their skill set. There’s a method to our madness. They don’t think so, but there’s a method.”

Clare, with a sneaky smile on his face, pulls a phone from his pocket and reveals a personal project he’s been working on: the Game Jam App, a random generator of game design ideas. Generating a genre, mechanic, item and one random prompt, the app is meant to kick-start those who may be creatively stuck on a project. Clare said that for the next jam, the students will be going from three prompts to four, with one item randomly generated using the app.

As Clare approaches the head of the classroom, the chatter dies away. There’s no time for a pat on the back; last week’s jam project has just been completed and is already forgotten. It’s time to get back to work.

“Your game for next week must have the following: number one, a turkey bird,” Clare shouts as one student marks the requirements down on a large whiteboard.

“Number two, a bromance. Number three, underwater, and number four,” Clare delivers with a flourish. He clicks the game jam generator.

“’Dance, dance, dance?’,” Clare says triumphantly. “Question mark included.”

The chatter around the class begins again in the wake of the announcement. You can practically hear the gears churning as students scramble to choose partners and jot down initial ideas. Looking at the whiteboard, you’d be forgiven for thinking these four prompts were meaningless. But for someone in this room, it’s very possible they could be the first four steps to a career in the Toronto video game industry.