Mother of George Brown grad who died of fentanyl overdose becomes advocate in opioid crisis

UPDATED Sept. 19 with a comment from Toronto Police

To hear Jennifer Johnston recall details of her son Jonathan’s last months—losing a job, telling his mom that he had a problem, getting help and then vanishing twice—the steps leading up to his death are evident. But that’s in retrospect.

As it’s happening in real time, it’s much harder to see it coming.

Jonathan, 25, was found by strangers at the corner of King and Yonge on April 20, 2016 with a lethal dose of fentanyl in his body. Now his family is trying to make sense of a skilled chef, beloved friend, brother and son losing his life to an addiction and all the ways it could have been prevented.

“It’s one of my greatest regrets,” Jennifer said. “I wish I had been more proactive with it, but he assured me he was doing fine and unfortunately I believed him.”

The words used to describe Jonathan, a graduate of George Brown College’s culinary program, read like a personality wishlist; driven, self-sufficient, generous, successful and happy.

More than a year after his death, other words come to mind as well; troubled, badly missed and one of many victims in the ongoing overdose crisis in Canada.

Jonathan was one of the 2,458 opioid-related deaths in Canada in 2016. And with Health Canada signalling that they expect an even higher opioid death toll this year, his mother is working to make sure more people don’t die.

“If his story could help even one person and save another mother from going through this, then it makes it a little less painful,” she said.

Since Jonathan’s death, his mother Jennifer has become an advocate for harm reduction. Photo: Steve Cornwell / The Dialog

His mom said Jonathan always wanted to be a chef. As young as 10 years old, he asked for ramekins for Christmas so he could make crème brûlée. Then he started to make meals for his family.

After high school, he insisted that George Brown’s culinary program and Toronto were where he needed to be. Despite his mother’s wishes for him to go to college closer to the family’s home in St. Catherines, Jonathan couldn’t be deterred.

When he graduated, Jonathan landed in the kitchens of upscale restaurants like La Société at The Adelaide Hotel (formerly Trump Hotel) and at Origin which was owned by Master Chef Canada judge Claudio Aprile.

“He was the life of our house,” said Jonathan’s sister Sarah. “He was the one who made it when we all of us just kind of sat here in St. Catherines and worked our minimum-wage jobs.”

Sarah has closely followed her eldest brother’s culinary ambitions, however. This year, she was accepted into the bakery and pastry program at Niagara College. With her and Jonathan’s skills being complementary, they had talked about working together in the future.

“We planned on having a nice place one day if all things went right,” she said.

When Sarah answered a call from her father at five in the morning last April, she said that she immediately wondered if Jonathan was still alive. Even after the news of his death hit, Sarah was in disbelief.

“Honestly I didn’t believe it until I saw his body at the funeral,” she said. “I believed he was still in Toronto and that (the body) was just a John Doe.”

More than year since his death, Sarah said she hopes the family will move on from the grief of losing Jonathan and focus on the memory of his life.

“For a straight year now, it’s definitely been a hell of a roller-coaster,” she said.

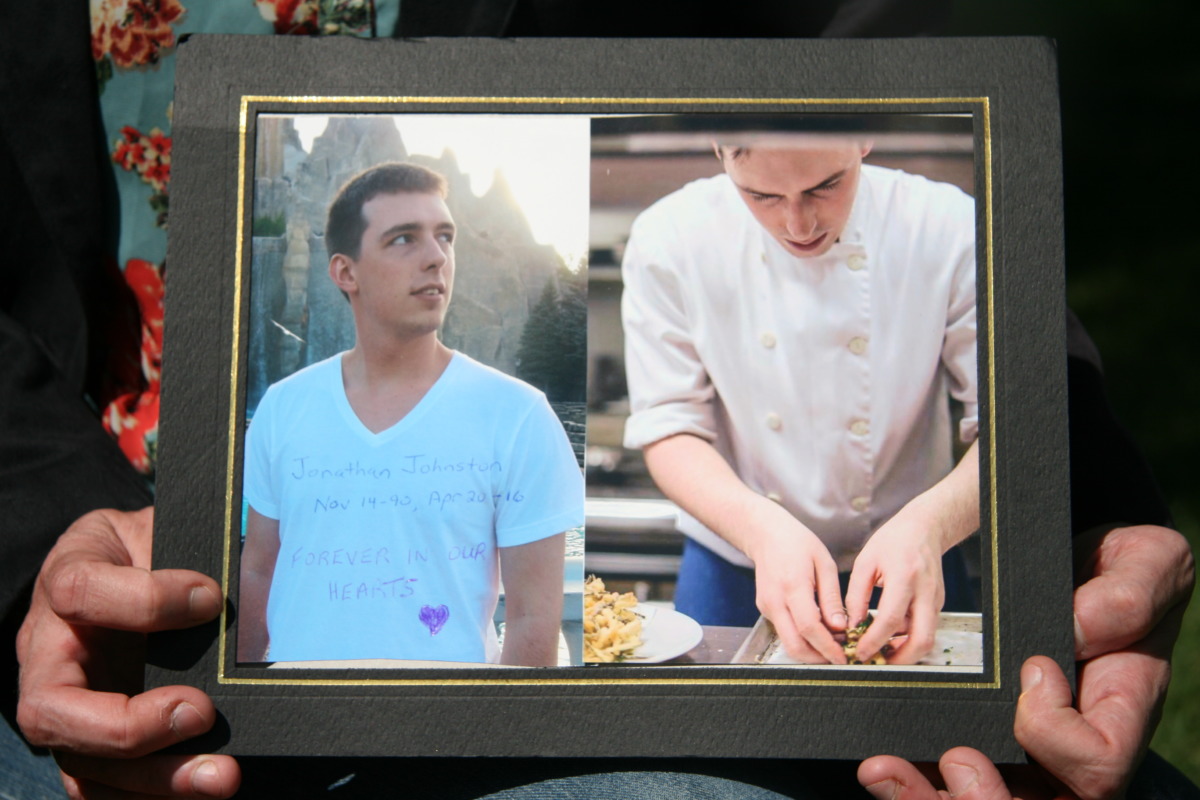

A family photo of Jonathan Johnson shows him at Canada’s Wonderland and working in a kitchen with an inscription reading “forever in our hearts.” Photo: Steve Cornwell / The Dialog

According to Health Canada’s report on opioid deaths in 2016, the Yukon, Northwest Territories, BC and Alberta share the highest rates in Canada, with over 10 per 100,000 in each province’s population having an opioid-related death. The Canada-wide rate by comparison was 8.8 per 100,000 people.

The report noted that no data is currently available from Quebec.

While the signs of an overdose crisis began in BC, Leslie McBain, a co-founder of the harm reduction group Moms Stop the Harm, said Ontario should have seen the crisis creeping into the province.

“If the people in the business of looking at addictions and overdoses had been on the ball they would have known that this was going to hit Ontario, maybe not as badly as BC but it was going to come,” McBain said. “And sure enough, it has.”

McBain said that there has been an increase in people from Ontario, as well as many parts of Canada, asking to join Moms Stop the Harm. The group advocates for harm reduction and revamping of treatment options for users, so that when they reach out for help they get it immediately and on terms that work for them.

“We want people to know that it can be anyone’s child and it is anyone’s child or partner,” McBain said.

Jennifer Johnston has joined Moms Stop the Harm in Ontario.

Public Health Ontario recorded more than 850 opioid-related deaths in the province in 2016, a 19 per cent increase from 2015, the largest annual increase ever recorded.

In total, between 2003 and 2016, Ontario has had an estimated 7,694 opioid-related deaths.

In Toronto, Ward 20 councillor Joe Cressy said that the city has been facing an overdose crisis for a decade. But Cressy, who is the chair of the city’s drug strategy implementation panel, noted that fentanyl has created a new at-risk population.

“With the emergence of fentanyl being cut and laced into recreational drugs, we now have habitual and recreational drug users at a huge risk of a fatal overdose,” Cressy said.

The city, province and Health Canada have approved three supervised injection sites for Toronto, but to date, only one official site has been opened at The Works at 277 Victoria Street near Ryerson University. An unsanctioned overdose prevention site, operated by volunteers, has been open in Moss Park since Aug. 12.

One of the city’s supervised injection sites is slated to be in Cressy’s ward and he said that the residents in the area have been positive about it.

“The most common response I heard was that drug use is already in our community, we already have discarded needles in our childcare play areas, in our alleyways, in our washrooms,” Cressy said. “This will not only help to improve the health of the people that use drugs, it will reduce discarded needles in our neighbourhoods.”

In August, the Ontario government announced $222 million in additional funds over three years towards fighting the opioid crisis. The new funding includes producing more naloxone, a drug which counteracts the effects of an opioid overdose, and hiring more harm reduction workers.

While Jennifer Johnston believes that views are starting to change on drug use, she was troubled by the response of doctors to Jonathan when he tried to get help. When he died, Jennifer said she felt that the police “devalued” her son.

According to her, the police declared Jonathan a John Doe even though he had his health card with him. The police also had Jonathan’s body for two days without alerting the family, Jennifer said.

“I called them out, I said ‘why was he declared a Jon Doe?’ ” Jennifer said. “I mean if he died in a car accident and you had his health card, I guarantee that you would have found us within a few hours.”

Mark Pugash, director of corporate communications with the Toronto Police Service, said that the police did identify Jonathan, and taking two days to alert the family is reasonable given how common the name of the deceased was.

“Notifying next-of-kin whether it’s in a crime or any other situation is at the top of the list and it certainly sounds in this case, given what the officers had to work with, that they gave it the attention that it deserved.”

Pugash added that it’s unfortunate that Jennifer feels that police “devalued” her son, but that isn’t the information that he received from the officers who investigated Jonathan’s death.

Jennifer has requested the police report of Jonathan’s death, but it hasn’t arrived by press time.

Even though Jennifer said she resents being put into this position by government inaction, she recognizes that as a mother who has buried her son, she and other moms have power to make a difference.

“I believe that there is no better advocate than a grieving mother,” Jennifer said. “The stories are so heartbreaking that people stand up and pay attention. You realize that this could be my kid.”

This month, Health Canada published an alert about drug and alcohol use during orientation that highlighted information about how to identify an overdose.

The alert also said that the federal government is “deeply concerned about the growing number of overdoses and deaths caused by opioids, and is committed to protecting the health and safety of Canadians from the risks posed by opioids and other drugs.”

A spokesperson for the college said that security at George Brown does not have naloxone. They added that the college takes the issue seriously and has been working with Toronto Public Health on developing protocols.

According to spokesperson, Christine Crosbie, OCAD has been working to address the opioid crisis with “an emergency and preventative perspective” through it’s health and wellness centre.

“There are naloxone kits on site at the centre and our nurse and physician are trained to administer in the event someone comes into the centre presenting with an overdose of fentanyl or opioids,” Crosbie wrote in an email.

She added that the health and wellness centre does referrals to a nearby Shoppers Drugmart where folks can pick up naloxone kits and be trained on how to use them if they are at risk of having or witnessing an opioid overdose.

A spokesperson for Ryerson University said that while their student leaders are not trained on how to administer naloxone, they are trained to spot students in distress and call on Ryerson’s emergency medical staff when needed.

The Eyeopener student newspaper reported on Sept. 15 that the Ryerson Student Union plans to train its equity centre staff to carry naloxone.

“I would like drug use to be looked upon as a disease and not a moral failing,” Jennifer said.

She has taken training on how to administer naloxone and is considering opening up an unofficial overdose prevention site in St. Catherines.

“It shouldn’t be up to grieving people to move this issue along,” she said. “Our politicians are dragging their feet.”